Money, an essential tool in the tapestry of human civilization, has continually evolved, adapting to the needs and advancements of societies. From barter systems to precious metals and eventually, to paper notes, the journey of the currency reflects our changing world. In this modern era, we encounter “fiat money” – a form of currency without intrinsic value, yet crucial in global economies. This article explores the concept of “what is fiat money,” unraveling its significance and the mechanisms that define its role today

What is Fiat Currency?

Fiat currency is a type of money that is issued by a government and not backed by a physical commodity like gold or silver. Its value is derived from the trust and confidence that people place in the government that issues it. Unlike commodity-based currencies, fiat money is supported by the economic strength and stability of the issuing government. This type of currency gains its usefulness from its widespread acceptance as a medium of exchange for goods and services

How We Got Here: A History of Money

The history of money is a fascinating journey from basic barter to the complex fiat currencies of today. Initially, barter was the primary method of trade, where goods and services were directly exchanged without any standard medium of value. This system, however, had inherent limitations, notably the need for a ‘double coincidence of wants’ – the unlikely scenario where two parties each possess something the other desires. Another reason why barter was not scalable is because it necessitates keeping track of the exchange rate between all the goods and services in the market. As societies evolved, so did the concept of money. The transition from barter led to the use of collectibles as a medium of exchange. These were items like shells, beads, or even livestock, which held value due to their rarity, beauty, or cultural significance. Collectibles represented an early form of money that carried intrinsic value, making transactions simpler and more reliable compared to barter.

The next significant advancement was the adoption of gold coins as a universal medium of exchange. Gold, valued for its rarity and beauty, was easy to work with and resistant to corrosion, making it an ideal material for minting coins.

Coins were a big step up in the history of money, but they lacked the portability that paper money provides. Paper money started popping up across the globe starting with the Song dynasty in 7th century China, representing copper deposits made by merchants and wholesalers. Later, in the 13th century, adventurers like Marco Polo enlightened Europe with tales of paper money and its use in the East. In the ensuing centuries, banking would evolve across both East and West. Banking and accounting took a giant leap forward in Renaissance Italy, two centuries after Marco Polo left the same Italian shores for his Eastern adventure. Finance flourished in Florence, where powerful families like the Medicis founded banking empires that would leave a lasting impression to this day. Double-entry accounting, the system of recording debits and credits that are used to this very day, was one of the innovations introduced in the golden age of Italian banking.

Another notable stop on the history of money is 17th-century London, the place where modern finance developed its institutional heft. In a century that saw a civil war in England, during which King Charles I seized the national mint and stopped the flow of coins to the Crown’s creditors, the goldsmiths took a central role in regulating commerce in the Kingdom. From the safe storage of species to transferring money from town to town, dealing in bullion, and exchanging foreign currency, the goldsmiths concentrated many of the services we would associate with modern-day banks. Receipts issued by London’s goldsmiths eventually evolved into proper banknotes. Cheques also got their start in the same period.

Such an arrangement, where private entities would issue currency backed by hard assets like gold and silver, became widespread both in Europe and in the New World. Traders in pre-revolution America had a choice between gold and silver coins, bills of credit, and even commodity money when conducting their business. Tobacco was a favored cash crop of the founding fathers like Washington and Jefferson. At the same time, each one of the thirteen colonies issued its own currencies. Early attempts at creating a central bank failed, such as the second Bank of the United States which lasted only 17 years before being put out of action by President Andrew Jackson.

After centuries of trial and error, the US finally established a central bank in 1913 with the creation of the Federal Reserve. America’s central bank plays a pivotal role in the nation’s monetary policy and financial system stability. Its actions are crucial in influencing economic conditions, primarily through manipulating interest rates and controlling the money supply. In the early days, the Fed was limited in its money printing power by the need to maintain the dollar’s peg to gold. However, during the “Nixon Shock” of 1971, President Richard Nixon suspended the US dollar’s convertibility into gold, marking the end of the post-war gold standard. Thus began the era of fiat currencies where the value of money is not backed by physical commodities.

Does Fiat Money Lead to Inflation?

Yes, central banks expand the supply of fiat money, which leads to inflation when an expanded money supply chases the same goods and services in the economy

The history of money is replete with instances of inflation, often as a result of governments printing money excessively.

Notable examples include

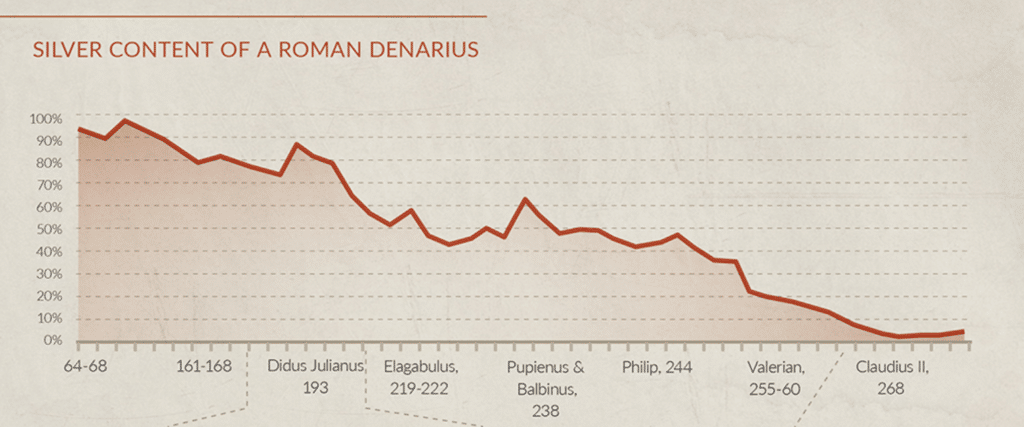

- Ancient Rome is a classic case of currency debasement leading to the fall of an empire. As the Roman Empire expanded, so did its need for funds. The problem was that Roman rulers were limited in their ability to issue more currency by the natural scarcity of gold and silver that made up their coins. Emperors began debasing silver coins with cheaper metals to finance their pet projects, leading to rampant inflation and contributing to Rome’s eventual economic collapse. By the time the Empire collapsed, Roman coins were almost exclusively made of cheap metals like copper, without any silver contents.

- The Bank of Amsterdam, initially a paragon of banking stability, fell into the trap of its success. Fueled by New World gold and silver, it attracted deposits with favorable terms. On the other hand, the Bank of Amsterdam was lending out money to new joint-stock companies like the Dutch East India Company. The bank realized that it could lend out more money than it had on hand. But overconfidence led to overextension. Large unsecured loans made to the Dutch East India Company never made it back to the Bank of Amsterdam at the end of the 18th century. Bogged down by corruption and growing costs, the first joint stock company would eventually dissolve in 1799, with the Bank of Amsterdam following it to the corporate graveyard 20 years later.

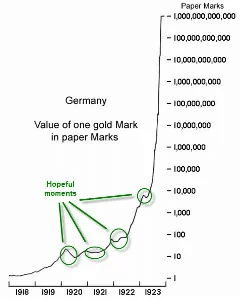

- After World War I, Weimar Germany faced severe economic challenges and resorted to printing money excessively to pay debts and reparations. This led to one of history’s worst hyperinflations by the early 1920s. The German mark’s value plummeted, with prices soaring rapidly, rendering the currency nearly worthless. By 1923, hyperinflation had escalated to the point where money was carried in wheelbarrows for basic purchases, and savings were obliterated, fueling social unrest and setting the stage for political upheaval.

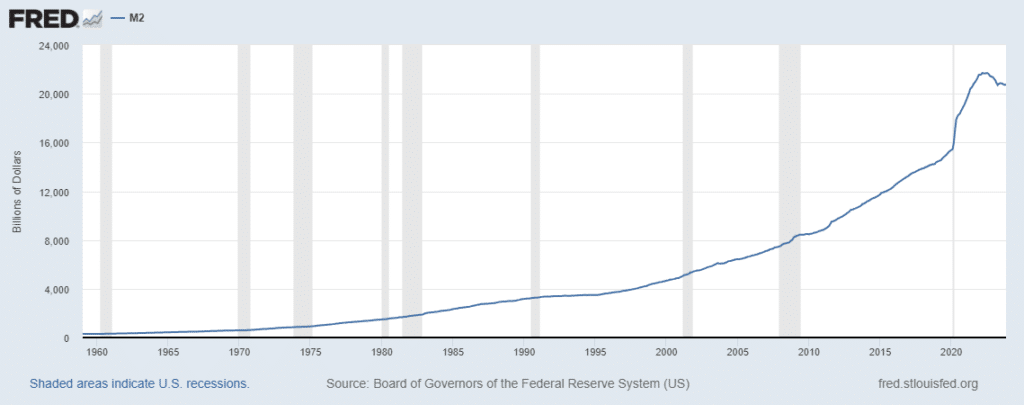

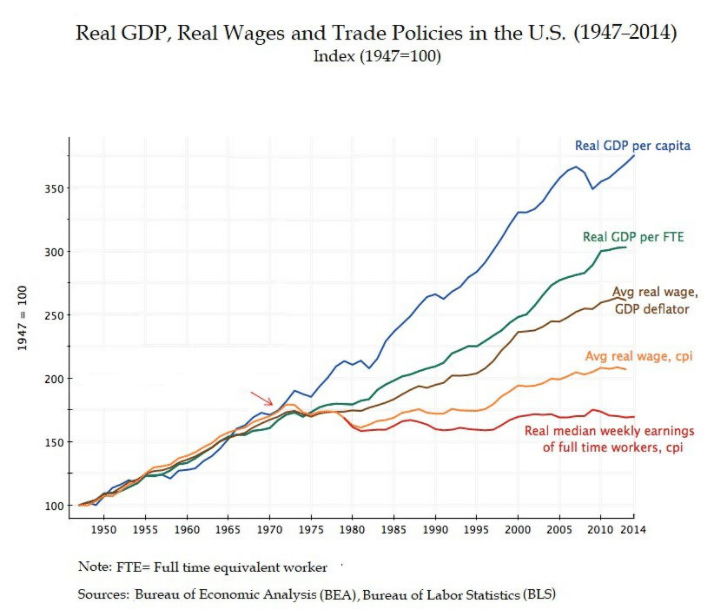

The problem of inflation has only gotten worse since we entered the fiat money era. Ever since 1971, when Richard Nixon unpegged the dollar from gold, the Federal Reserve has had unchecked money-printing powers. When the Fed increases the money supply faster than goods and services, inflation usually follows. Historically, central banks have printed money in crises, like during World War 2 and the 2008 recession, leading to reduced dollar value. The Federal Reserve’s response to COVID-19, however, was unprecedented: about a quarter of all circulating dollars were created in 2020-2021, marking an aggressive phase of monetary expansion.